Score Orders

Scores and performance materials, both printed and as pdfs, are available for sale on request. Please email info@stephengorbos.com for all inquiries.

Category Archives: Vocal

Video of The Initiation performance

Back in November The Initiation went up for one performance at the Georgetown Waterfront Park Labyrinth. This site-specific project, in the city I’ve lived in for almost 10 years, is a type of collaboration I’ve wanted to engage with for a long time. I was so happy with the results (and that the weather played nice). Below is a full video of the performance. While I’m certainly not abandoning traditional concert hall projects or anything, I really hope to do this type of work again soon. Big thanks to sculptor Dawn Whitmore for thinking this whole thing up, and to the amazing singers that put in so much time to pull this off.

The Initiation

I am very excited to present my newest collaboration, The Initiation, with sculptor Dawn Whitmore. Dawn commissioned me to make a piece for four singers that is intended to be performed with an amazing wooden sculpture of ladders that she’s been making. We are putting together a free outdoor performance on November 18th at the Labyrinth at the Georgetown Waterfront Park in DC. The music should start as the sun goes down, ca. 4:45. We’re inviting people to come check out the sculpture starting at 4:00pm. Below is a preview video Dawn made of the sculpture with a bit of my music, and here’s a link to read more details at Dawn’s site. I’m really excited to be doing something site-specific and outdoors in my city, and, I couldn’t be happier with the merry band of singers we’ve gathered for the event: Rachel Evangeline Barham, Allison Clendaniel, Shauna Kreidler Michels, and Deborah Sternberg are killing it. Hope to see you there! If you miss it, we are planning more performances for the spring (stay tuned).

New Recording: Such sphinxes as these

Such sphinxes as these obey no one but their master, my new vocal octet and longest title to date, was premiered last week by the inimitable Brad Wells and Roomful of Teeth. Click here to listen to the performance and read more about the piece. Special thanks to the Beinecke Library at Yale University, who, along with hosting the concert, put the Voynich Manuscript on display as part of their current manuscript exhibition.

Such Sphinxes as These: Composing the Voynich

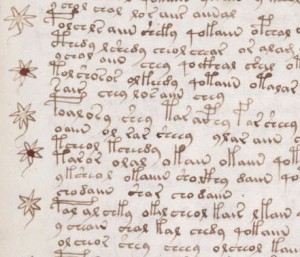

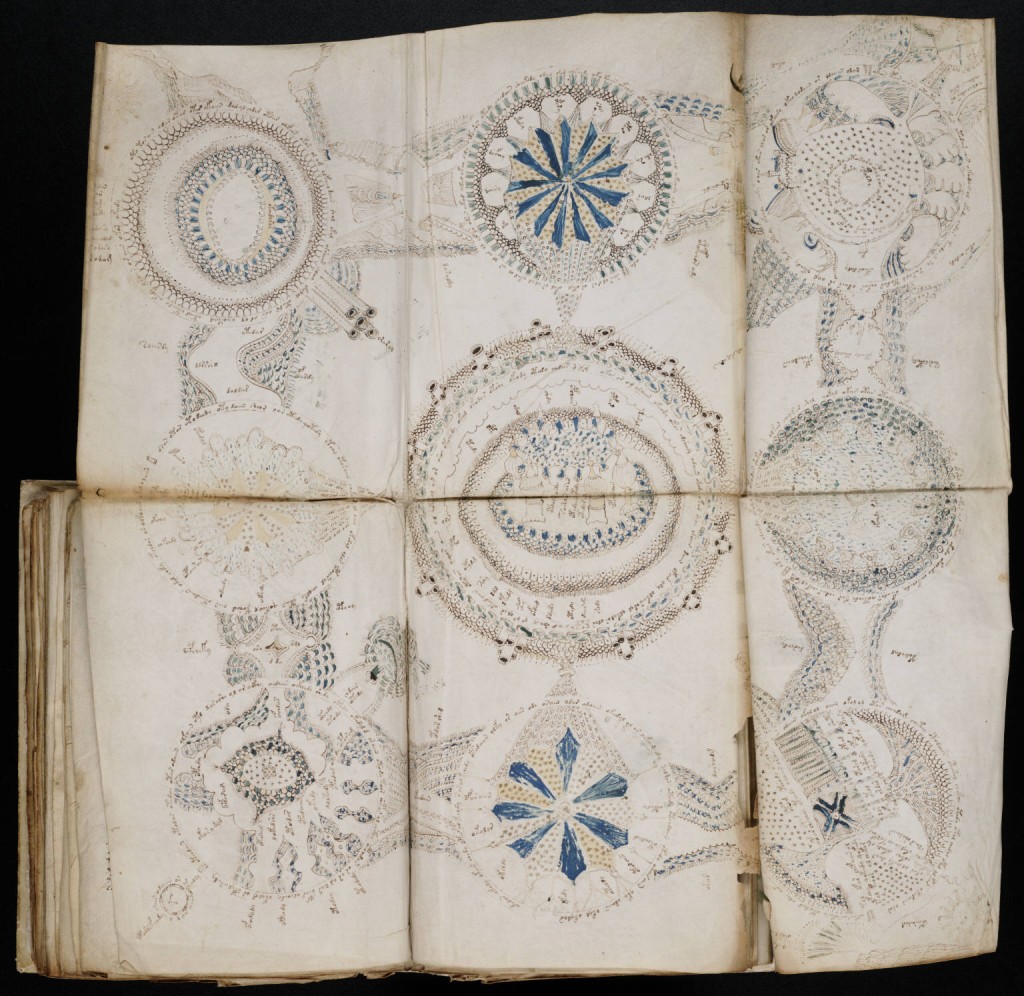

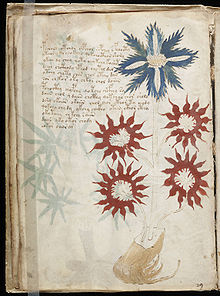

I just finished a new piece for Roomful of Teeth, an amazing vocal octet led by conductor Brad Wells. Inspired by the Voynich Manuscript, my piece makes use of several of the non-Western vocal production techniques that the group specializes in (yodeling, throat singing, and overtone singing). What follows is a lengthy program note: hopefully it will inspire a few readers to come check out the premiere in New Haven in a few weeks! Pics of the Voynich Manuscript courtesy of the Beinecke Library at Yale.

The Voynich Manuscript has piqued human interest since it first surfaced at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in the late 16th Century. (Radiocarbon dating completed in 2011 has dated it to the early 1400’s.) The manuscript’s florid script has remained completely indecipherable: perfectly legible (and resembling some western scripts of the period), the characters that make up the script do not add up to any known language. Indeed, it’s the lavish illustrations (present on every page, some of which foldout to the size of several pages) that have led to the general consensus to label some sections as herbals, astronomical, biological, cosmological, pharmaceutical, and recipes. Like the script, the illustrations have also resisted complete explanation: the plants in the herbal section are like none found on this earth; likewise, the astronomical charts do not belong to anything in our heavens charted by astronomers. These curiosities have prompted some to theorize that the Voynich is nothing more than an elaborate hoax, likely made by alchemists looking to extort money from Rudolf II. Yet some of the foremost minds in cryptology, from the 16th c. to the present day, believe that the text is an elaborate code. Linguists have found that the ordering and frequency of characters in the script have all the qualities of language; analysis of the writing reveals it to be in the hand of someone practiced at writing this script fluently. Some believe it to be in a hybrid language, because of some similarities in morphology to language families in East and Central Asia. Others claim that the text is an example of transcribed glossolalia, or even that the book was deposited on our planet by aliens. The Beinecke Library at Yale, where the manuscript has been part of the collection since the 1960s, gets regular requests from individuals wishing to ingest pieces of the manuscript (or, in some cases, just lick), inspired by a belief in its healing properties.

The Voynich Manuscript has piqued human interest since it first surfaced at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in the late 16th Century. (Radiocarbon dating completed in 2011 has dated it to the early 1400’s.) The manuscript’s florid script has remained completely indecipherable: perfectly legible (and resembling some western scripts of the period), the characters that make up the script do not add up to any known language. Indeed, it’s the lavish illustrations (present on every page, some of which foldout to the size of several pages) that have led to the general consensus to label some sections as herbals, astronomical, biological, cosmological, pharmaceutical, and recipes. Like the script, the illustrations have also resisted complete explanation: the plants in the herbal section are like none found on this earth; likewise, the astronomical charts do not belong to anything in our heavens charted by astronomers. These curiosities have prompted some to theorize that the Voynich is nothing more than an elaborate hoax, likely made by alchemists looking to extort money from Rudolf II. Yet some of the foremost minds in cryptology, from the 16th c. to the present day, believe that the text is an elaborate code. Linguists have found that the ordering and frequency of characters in the script have all the qualities of language; analysis of the writing reveals it to be in the hand of someone practiced at writing this script fluently. Some believe it to be in a hybrid language, because of some similarities in morphology to language families in East and Central Asia. Others claim that the text is an example of transcribed glossolalia, or even that the book was deposited on our planet by aliens. The Beinecke Library at Yale, where the manuscript has been part of the collection since the 1960s, gets regular requests from individuals wishing to ingest pieces of the manuscript (or, in some cases, just lick), inspired by a belief in its healing properties.

Without a real stake in the outcome of Voynich interpretation, I find the subjectivity in all these interpretations beautiful and moving. The process of constructing meaning from the many variables at play in the manuscript made me think about the myriad approaches to constructing music. Why do certain notes and rhythms follow other notes and rhythms? Is a composer’s process ever completely explainable? There might be a code at work, but how deep does that code go, and could anyone ever actually crack that code? Does it even matter that the logic of the piece is perceived while experiencing it, and why might a listener privilege objective truth in considering music?

Roomful of Teeth has skillfully absorbed the means of vocal production from various cultures across the planet. What I found fascinating was how these techniques, divorced from their original cultural practice, could be assembled into some new language. How could I make sense of Tuvan throat singing layered on top of Swiss yodeling? There might be a logical grammar at work, but a beautiful assemblage of sounds might also just be a happy inspirational coincidence, never to be heard from again. The title of my piece, Such sphinxes as these obey no one but their master, comes from a letter written in 1666 by Jan Marek Marci. Marci, a Jesuit priest who possessed the book for a time in the mid-1600s, sent the book off to Athanasius Kircher in Rome, hoping he could make something of it. Kircher, known in his day as the premier Egyptologist, failed to make any headway with a translation.

Roomful of Teeth has skillfully absorbed the means of vocal production from various cultures across the planet. What I found fascinating was how these techniques, divorced from their original cultural practice, could be assembled into some new language. How could I make sense of Tuvan throat singing layered on top of Swiss yodeling? There might be a logical grammar at work, but a beautiful assemblage of sounds might also just be a happy inspirational coincidence, never to be heard from again. The title of my piece, Such sphinxes as these obey no one but their master, comes from a letter written in 1666 by Jan Marek Marci. Marci, a Jesuit priest who possessed the book for a time in the mid-1600s, sent the book off to Athanasius Kircher in Rome, hoping he could make something of it. Kircher, known in his day as the premier Egyptologist, failed to make any headway with a translation.

UPDATE: click here to listen to the performance.